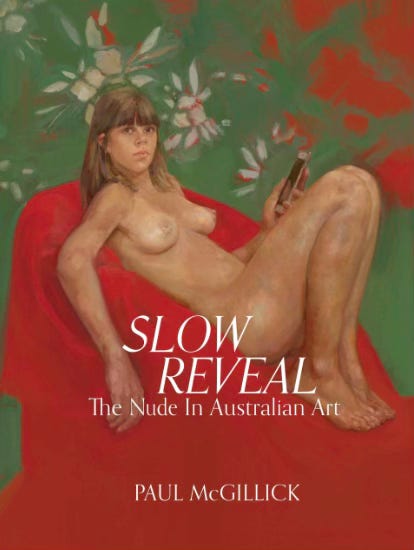

Last week, I agreed to launch Paul McGillick’s Slow Reveal: The Nude in Australian Art at Australian Galleries, Sydney. In response to a number of requests I’m posting a tidied-up version of that brief address. It’s not an essay or a review, so the tone may be a bit more conversational than most of the pieces on this site.

In 1990 the Manning Regional Art Gallery in Taree was planning – in time-honoured Australian fashion – to host an art prize. They asked me if I had any ideas about a theme, and I suggested the nude, or rather a prize that looked at Kenneth Clark’s famous distinction between the naked and the nude. They took up the idea, and a prize was born. It’s scary to think that was 35 years ago!

The nude is one of the classical themes of art, but it seems remarkable that it has always had such a minor presence in Australia. We have numerous competitions devoted to portraiture or landscape, but as far as I know, Taree’s Naked & Nude Art Prize is the only one that deals with the human body in a state of nudity, or semi-nudity.

It's just as remarkable that Paul McGillick’s Slow Reveal, is – to the best of my knowledge – the only dedicated study of the nude in Australian art. It’s an initiative that was long overdue, and Paul has taken up the subject with the kind of thoroughness the subject required. His book traces the peripatetic history of the nude from Thomas Bock’s private sketches of his wife, Mary Ann, made in the 1840s in old Hobart Town, to contemporary artists such as Dagmar Cyrulla and Bill Henson, who have made the nude a central theme in their work.

One sobering detail is a brief postscript in which Paul tells us that he approached 20 publishers before Yarra & Hunter agreed to take up the manuscript. This in itself reveals a range of attitudes towards the nude that one might have thought had no place in a society that imagines itself to be culturally and intellectually mature.

Read almost anything about the ancient Greeks and Romans, and it’s obvious that nudity was not seen as prurient. For the Greeks, the body and the soul were closely aligned. The athletes in the Olympic Games competed in the nude, and ideas of beauty were not pushed aside by base notions of carnality. “Eros” was a complex subject that didn’t simply translate into “sex”. I’m not sure we can say the same thing today.

In recent years, our fragile culture has become obsessed with grievances and victimhood. We imagine being “safe” as the highest of aspirations, even though it’s an utterly banal idea that invites mediocrity. There is a pervasive fearfulness that looks for problems where they don’t exist, imagining every male to be an incipient predator, and every nude to be a work of pornography intended to satisfy that predatory “male gaze”. The body has become offcially taboo again, in a way we haven’t seen since Victorian times, even as the Internet is awash with every form of pornographic gratification.

Add to this, the tedious identity obsessions that have invaded contemporary art and intellectual life and you’ll find many people who will complain that Paul hasn’t given sufficient prominence to Aboriginal people, queer theory, and other worthy categories. The fact is, “nudity” was not an idea that had much traction in traditional Aboriginal society, which had an uncomplicated atttude towards the body. Our own fears and fancies spring from a Judeo-Christian tradition that dates back to the Garden of Eden, when God thunders at Adam and Eve: “Who told you that you were naked?” (Genesis 3:10-11)

As for the “queer” lobby, Paul shows that the nude has been a theme for artists of both heterosexual and homosexual persuasions, but he avoids the more contentious theorising that seeks to find hidden sexual meanings in unlikely places. There’s really no better example than the AGNSW’s Queering the Collection program, that used rainbow labels to identify “queer” artists in the museum’s permanent holdings, such as Margaret Preston or Rupert Bunny, who are believed to have had homosexual liaisons in their younger days. For some reason, the AGNSW seemed to believe they were doing the artist a great service by ‘outing’ them in this way. I doubt the artists woud have agreed.

The idea that museums should be more concerned with the race or gender of the artist than their actual work, is entirely pernicious. It imagines itself as a very progressive thing, but it merely replaces one form of prejudice with another. What’s not racist about judging artists as good or bad in relation to their ethnographic origins?

At the risk of seeming conservative or old-fashioned, Paul sticks to a very basic understanding of what art is, and why we remain so fascinated by it. He believes it’s important to recognise “that art continues to effectively do what it has always aimed to do from cave paintings to the present day: to provoke us into reflecting on what it means to be alive on this planet.”

This should not be controversial. And neither should Kenneth Clark’s claim that over time the nude became an end in itself, as well as a way of reflecting on the human condition.

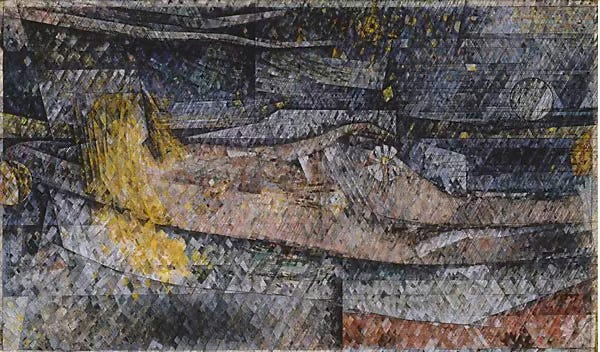

The merest glance at the images in this book shows us the wide range of styles, approaches and motivations that Australian artists have pursued in relation to the nude. It’s clear the nude cannot be reduced to any one thing or subjected to any textbook set of interpretations. How, for intance, could one compare one of Norman Lindsay’s leering, pneumatic pin-up girls, with an austere figure by Godfrey Miller, carved up into an abstract grid? There are works, such as Brett Whiteley’s, in which the body is depicted in a sensual manner, and ones in which the nude is largely a vehicle for a pictorial idea, as in the Cubistic images of Dorrit Black and Grace Crowley.

John Brack is one of the notable painters of the nude in Australian art, but there is a cerebral aspect to his work that keeps sexuality at bay. Ivor Hele, on the other hand - known for his conventional tonalist portraits (he won the Archibald prize five times) - painted nudes that were intimate, overtly sensual, and almost perverse in their fascination with fetish items such as stockings, underwear and less-than-classical poses.

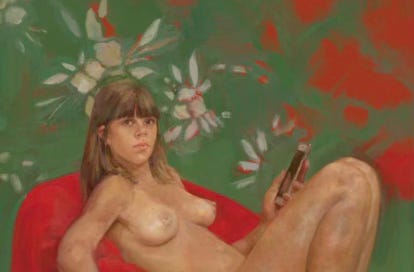

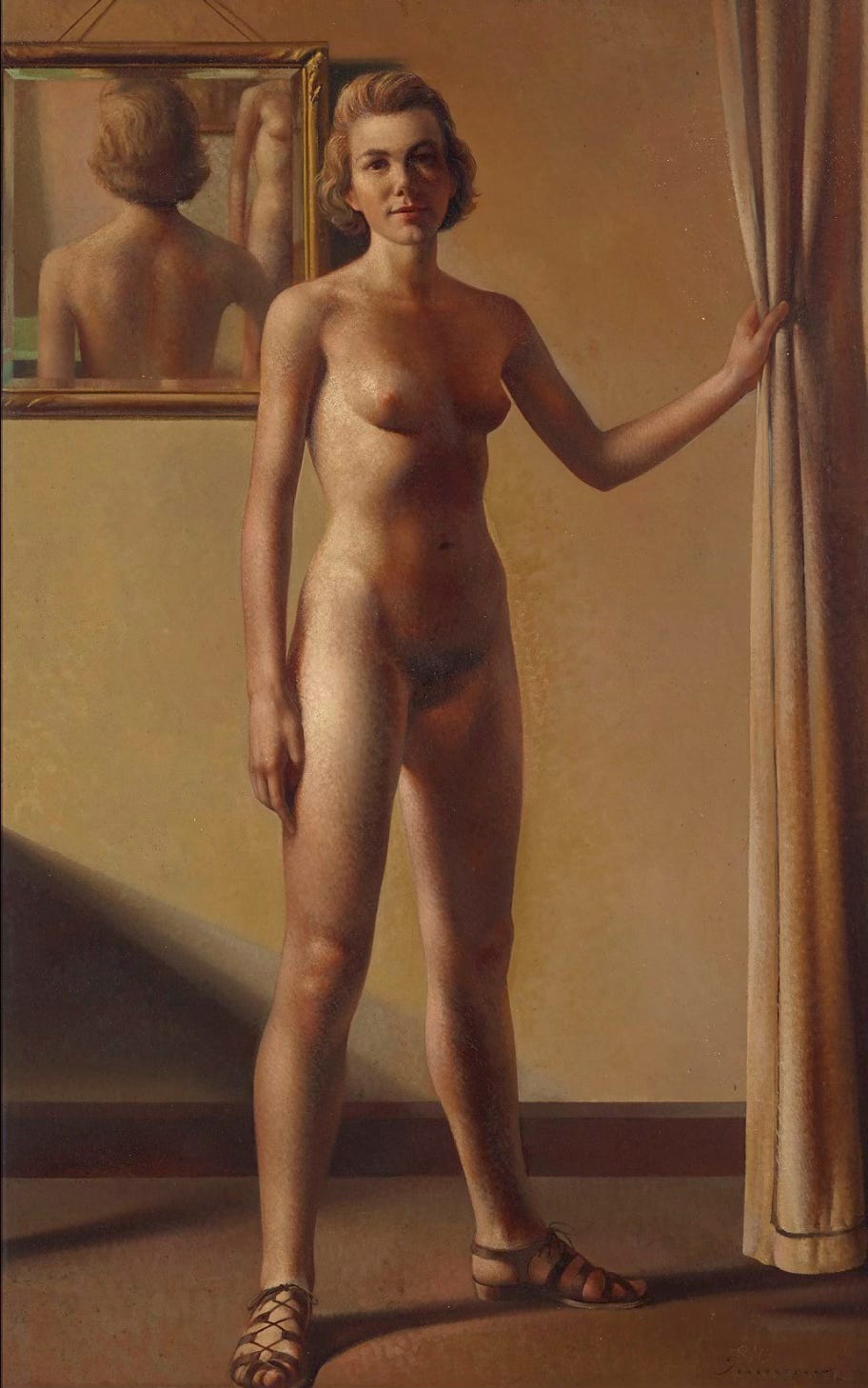

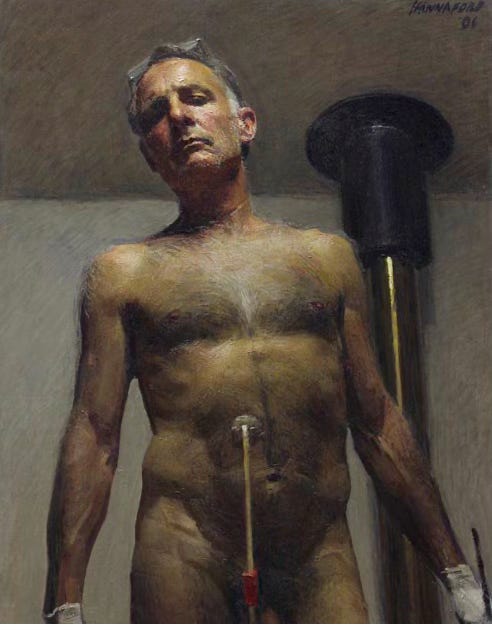

There are the emblematic Art Deco nudes of Rayner Hoff, and his students such as Jean Broome-Norton, intended to embody a vitalist philosophy, and the psychological nudes of Dagmar Cyrulla, who makes us feel we are only seeing one fragment of a larger story. And then there are those pictures Paul calls the “one-offs”, nothing more striking than Freda Robertshaw’s brash, self-confident full frontal, self-portrait of 1943, in which the artist’s shoes and neat hairdo, seem to emphasise her nudity. Another one-off, although not the only nude painted by this artist, is Robert Hannaford’s Tubes (2007), a self-portrait made while he was being treated for cancer, which shows a plastic tube protuding from his torso.

In a book like this, Clark’s division between the naked and the nude becomes impossible to avoid, although it’s open to interpretation. While the nude has overtones of tradition and social respectability, nakedness implies a brute honesty about the human body - literally having nothing to hide.

In the late Victorian era, and in the Paris salons, there was a great deal of hypocrisy involved in the painting of the nude, as classical or orientalist themes enabled artists to smuggle in the most titillating content. I was reminded of such last week in Broken Hill, when confronted with Arthur Hacker’s 1890 work, Vae victis! The sack of Morocco by the Almohades, woe to the vanquished – a rip-roaring scene of pale, scantily clad women and young girls being piled up like sacks of potatoes by evil-looking arabs.

Confronted by such outrageous double standards, one can appreciate the blunt honesty of a “naked” image by a contemporary artist.

But whether we wince at the soft porn peddled by the Victorians, or stand quizzically in front of a busy Godfrey Miller, surely Clark is right, when he says: “no nude, however abstract, should fail to arouse in the spectator some vestige of erotic feeling, even though it be only the faintest shadow – and if it does not do so, it is bad art and false morals.”

While acknowledging this insight at the very start of the book, Paul could be accused of underplaying it, in seeking to demonstrate the many and various ways the nude finds its place in Australian art history. Despite himself, he makes the nude respectable, when a large part of its appeal will always be the persistent, unnerving curiosity we feel about other human bodies.

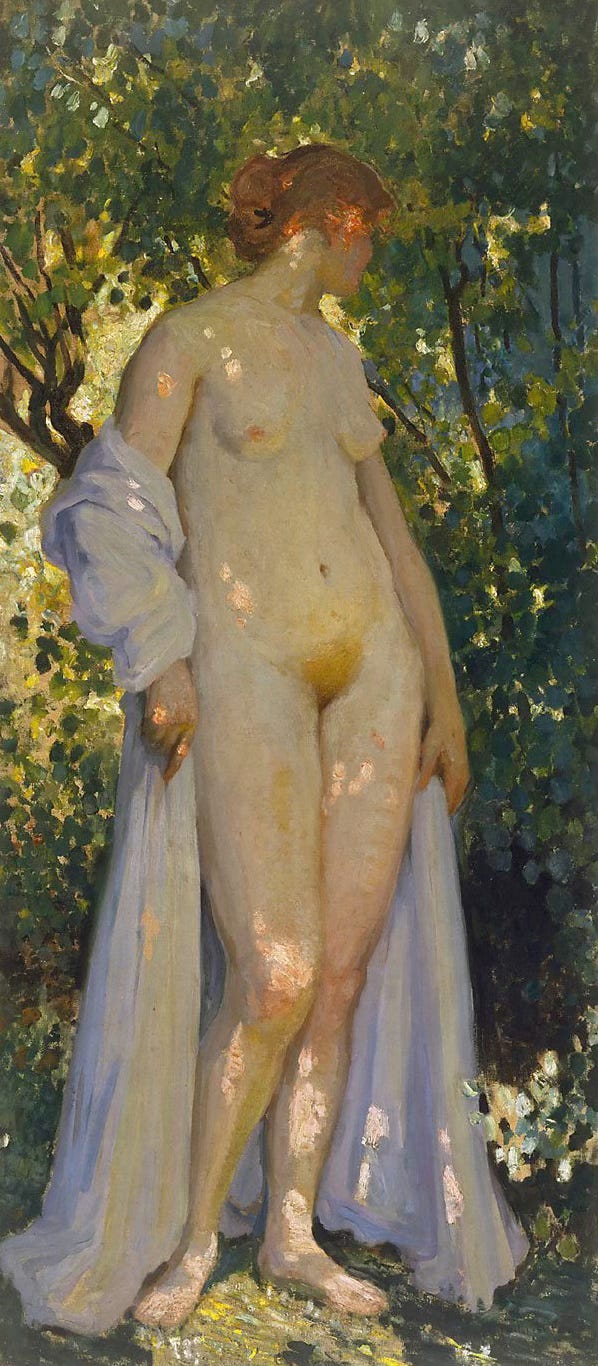

This feeling is not limited to the viewer but finds its way into many works in which we can sense the sexual tension between artist and model. I’ve always discerned a trace of that tension in Emanuel Phillips Fox’s paintings of Edith Anderson, whose red hair and red pubic thatch makes her instantly recognisable in so many paintings. There’s such implicit tenderness and sensuality in these paintings that Fox’s wife, Ethel Carrick, must have felt relieved when Edith got married to Penleigh Boyd and gave up the modelling.

Janet Cumbrae-Stewart’s exquisite pastels form another body of work in which we can feel the artist’s fascination with the young women who act as her models. The poses, the props, the play of what is revealed or concealed, testify to an interest that goes beyond aesthetics, giving these images a charge that hasn’t diminished over time.

Even John Brack’s works, in which he allegedly set out to “de-eroticise” the nude, still hold a residual erotic pulsation. It’s the very intensity of Brack’s probing, analytical eye we feel taking in every aspect of the model’s body, measuring and re-arranging it within the composition. By reducing the body to simple volumes, he makes us aware of how skinny or plump his subject might be, how far she deviates from the classical ideal. We feel these deviations as documents of real life – of nakedness, if you like – rather than the lies of art.

And so it is that we need to hail this long-awaited book, as an overview of a subject fundamental to art, but whose ultimate appeal goes far beyond artistic convention. The universality of bodily experience guarantees the undying appeal of the nude, even as we seek to marginalise the topic, or categorise it into oblivion. Reading Paul’s book made me think of many other works that could have been featured in its pages, suggesting there’s a big story yet to be told. For anyone who undertakes that task this book will be foundational. Indeed, it’s only after reading the book one realises that a foundation is precisely what has been missing all along.

Ladies, gentlemen & others, I give you Paul McGillick’s Slow Reveal: The Nude in Australian Art.

Slow Reveal: The Nude in Australian Art, by Paul McGillick, Yarra & Hunter Arts Press, 240 pp, AUD $79.95

Launched at Australian Galleries, Sydney, 11 April 2025