Ask most people about Pompeii, the Roman city buried by a volcanic eruption in 79 CE, and they think of those stony figures frozen in the moment of death as the full force of the explosion swept over them. There are five of these figures in Pompeii: Inside a Lost City at the National Museum of Australia – four people and a dog. They are not, however, the actual casts of those who died in the eruption, but resin copies, indistinguishable to the naked eye.

The decision not to allow the original casts to travel is mainly a matter of conservation, but it also connects with the hypersensitivities of our times which anticipate audiences swooning at the sight of human bones, a body cast or a mummy. As a result, the five figures in the Pompeii show are exhibited in a kind of enclosure, with the inevitable trigger warnings.

Are we so fragile nowadays that the merest hint of death will send us into a tailspin? Perhaps it’s the thought of those poor anonymous beings whose mortal remains have ended up in a museum that provokes a traumatic reaction. One could just as easily see this as a form of immortality. Maybe it’s better to be remembered in a museum than disappear into oblivion.

The bulk of this travelling exhibition, put together by the Parco Archeologico di Pompeii, originally for the Grand Palais in Paris, is devoted to life – the everyday life of the ancient Romans, how they worked and played; what they ate; how they worshipped their gods and ran their households.

This is not the first Pompeii exhibition to be shown in Australia. In 1994, the Australian Museum hosted a show called Rediscovering Pompeii, while in 2009 Museum Victoria gave us A Day in Pompeii. The current exhibition is not merely more-of-the-same, because our understanding of the “lost city” advances all the time. Approximately a quarter of the site has yet to be excavated and analysed by the archaeologists, and each discovery raises new questions.

Classicist, Mary Beard calls it “the Pompeii Paradox” – that as excavations continue, “we simultaneously know a huge amount and very little about ancient life there.”

We know that a major earthquake in 62 CE inflicted huge damage on the city, making it hard to judge the state of affairs 17 years later, when Vesuvius erupted. Buildings ruined by the earthquake may have been left unrepaired or put to new uses. People who lived in the city may have moved out, changing the demographics.

We also need to be aware that at an upper estimate, fewer than 2,000 people died from a population that could have been as high as 20,000 or even 30,000. Most citizens seem to have fled at the first signs of trouble. Among those who remained, many would have been preparing to evacuate when they were overcome by the “pyroclastic flow” which struck with such speed and violence there was no chance of escape.

This is the aspect of the Pompeii story that plays most vividly upon our minds. In Australia, the prevalence of bushfires and floods has allowed us to imagine what it would be like to have only minutes to grab your most treasured possessions and make a run for it - which is precisely what a lot of unlucky Pompeiians were doing when they were engulfed by ash and lava. Over the centuries we recognise their fear and panic. We think of those who got away, those who sat gazing in horror from a distance as their city was swallowed up.

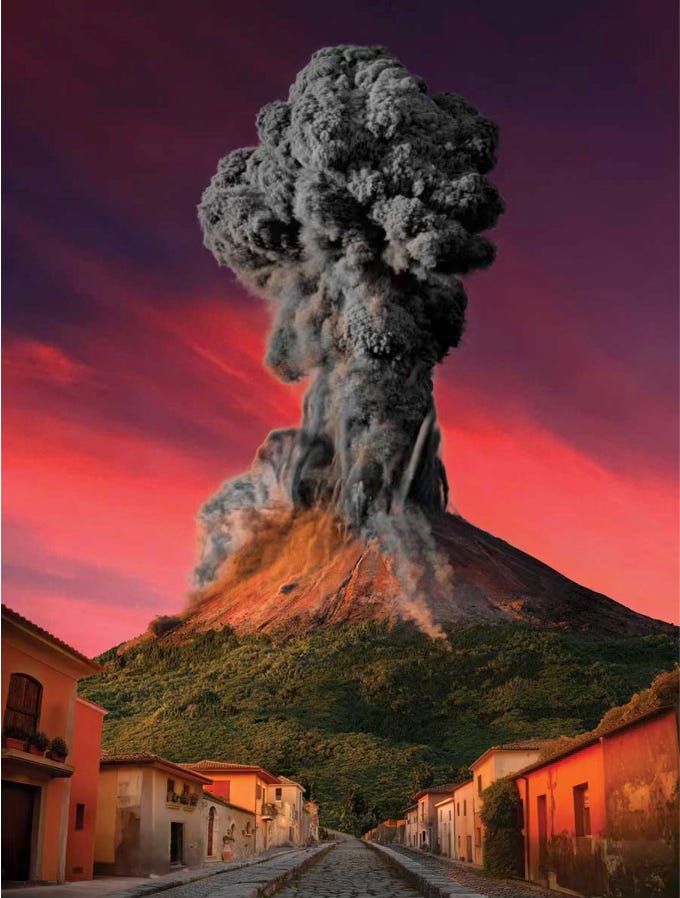

The NMA exhibition is arranged in a manner that mimics the layout of a street. We stroll down a central corridor, with shadows of Pompeii’s inhabitants flickering on either side. Looking towards the end of the room, we see Mount Vesuvius projected on a grand scale. At regular intervals the volcano begins to smoulder, and rumbling noises are heard. Suddenly it erupts with colossal force, engulfing the gallery in clouds of billowing smoke. But as these clouds are only projections, we don’t need to flee or reach for our hankies.

The illusion would be even more effective in a space less cavernous than the NMA’s temporary exhibitions gallery. These high-ceiling chambers are the least sympathetic venues to show art and artefacts, an observation lost on those who think they can “revitalise” the Powerhouse Museum in Ultimo by replacing 20 conventional galleries with three large volumes. Mount Vesuvius couldn’t complete a more effective work of destruction.

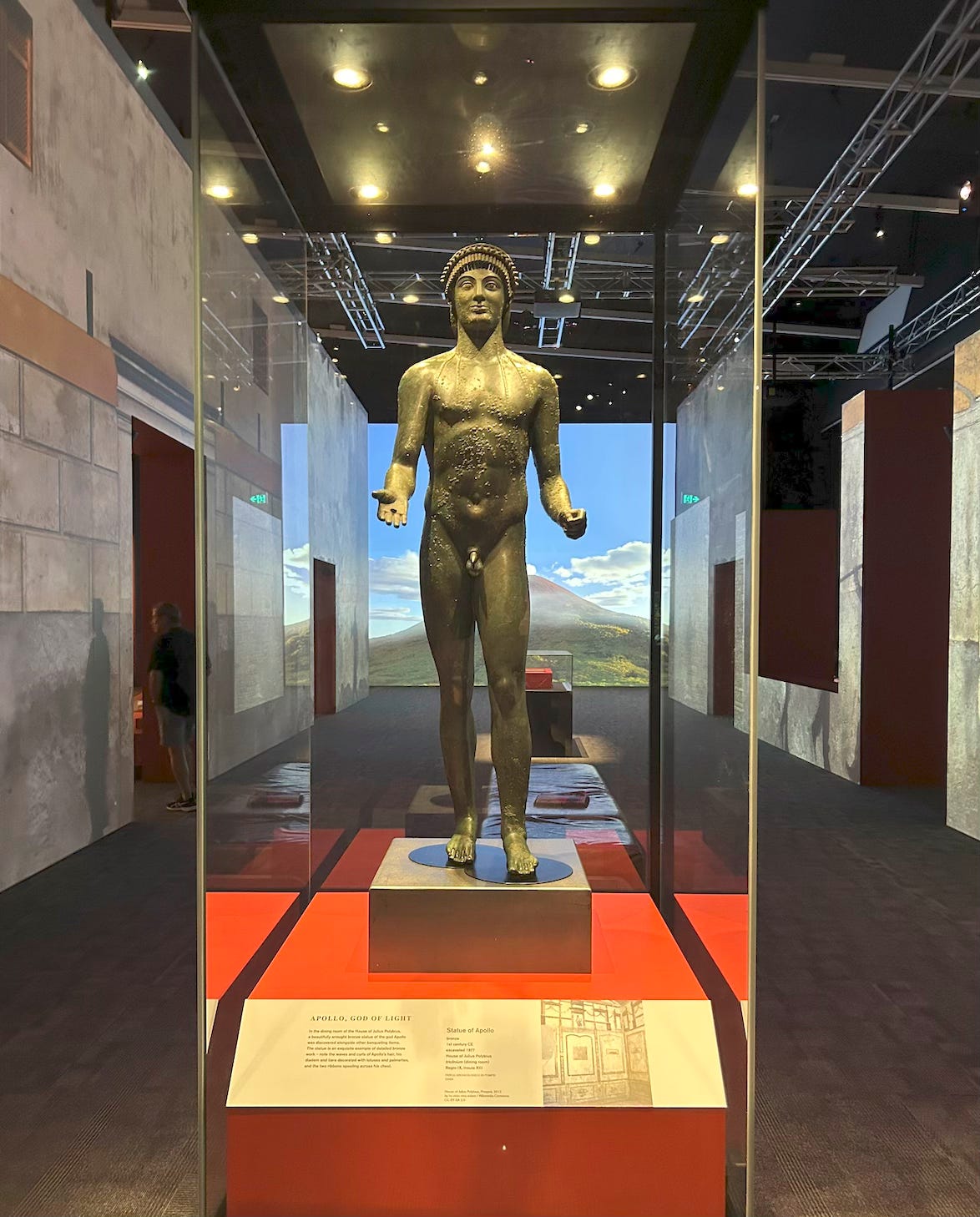

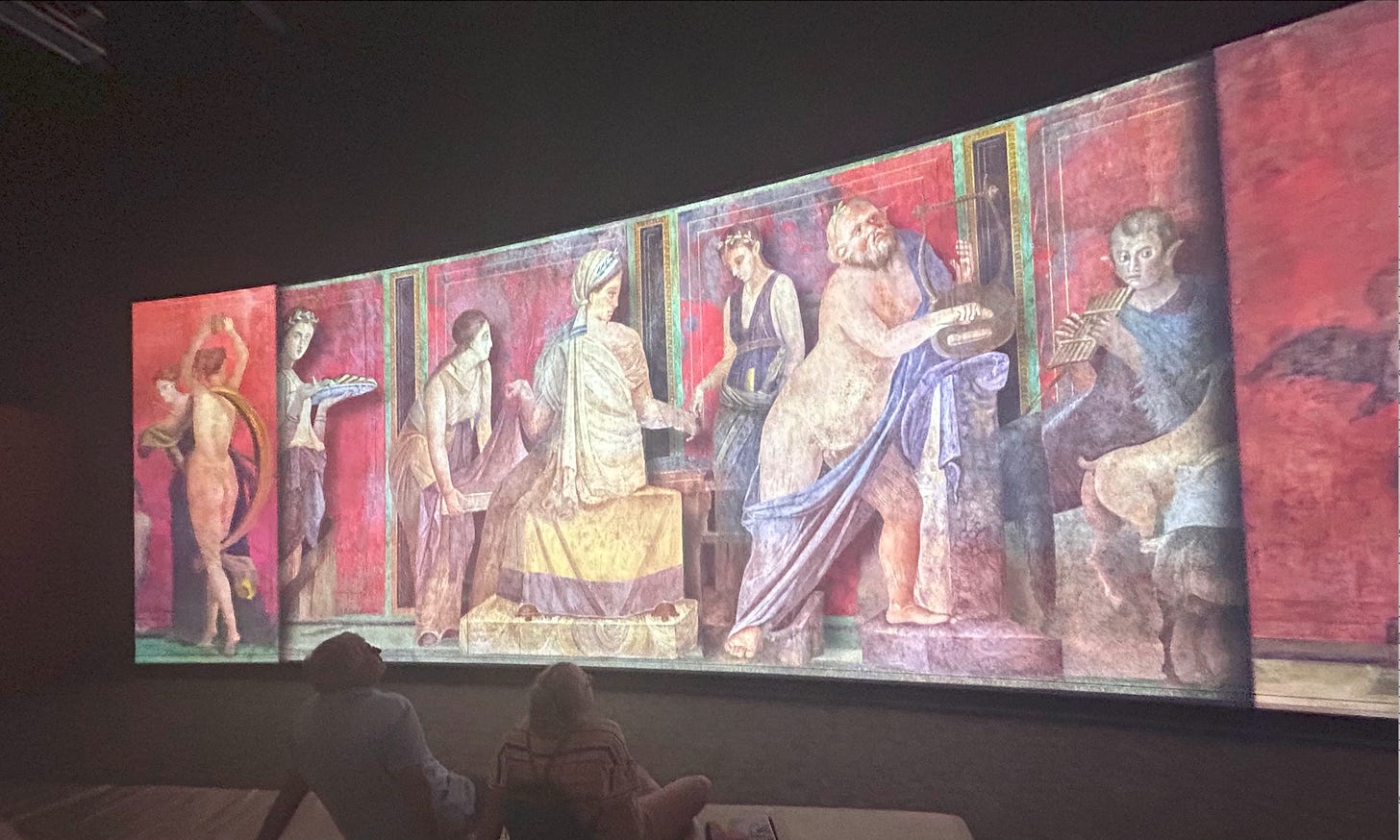

Even though I’m always drawn to the original artefacts in these shows – the tiny bronze statuettes of gods, the mosaics and marbles – the large-scale video projections are probably the highlights. One room features a shifting display of panoramic images of frescoes found on the walls of villas. There are distinctly different styles and themes in paintings from the House of the Vetti, the House of Adonis Wounded, The House of Venus in the Shell, and others. These wall paintings were an important feature of the Roman interior, denoting wealth and status. They might portray favourite deities, episodes from literature or the theatre. They provide clues as to how people lived, and the bawdy humour of the period.

With Pompeii currently featuring on the current HSC Ancient History syllabus for NSW, it’s the perfect time for the NMA to be hosting such an exhibition. The museum might have seen this as an opportunity to sell catalogues, had they chosen to publish one. Instead, they have put out a special edition of the museum magazine which includes extracts from the Grand Palais catalogue combined with a mish-mash of local content, including an essay on volcanic activity in Australia, an Aboriginal elder from Far North Queensland discussing a volcanic Creation story; TV chef, Silvia Colloca, talking about Italian cuisine; horticulturalist, Paul Bangay on Italian gardens; and a piece on architect, Enrico Taglietti, who designed the Italian embassy in Canberra. The cover image is by Andy Warhol.

None of this is entirely without interest, but its relevance to an exhibition on Pompeii is questionable. From a museological perspective, such an anthology is no replacement for a checklist of items in the show, an overview of the history of Pompeii, essays on key pieces, and a bibliography. Instead, we get a spoonful of scholarship and cartload of lifestyle. The exhibition store has the usual junk, but why wouldn’t they stock Mary Beard’s Pompeii: The Life of a Roman Town (2008), a compact, well-written book that includes everything one needs to know on the topic?

What we see here is part of a dangerous trend in Australian museums, where scholarly engagement (boring) is being sacrificed in favour of a weekend magazine approach that is obviously deemed more accessible. This is a form of dumbing-down, and it’s utterly provincial. The publication that accompanies this show tells us as much about Canberra as it does about Pompeii!

None of this is necessary because Pompeii – “the lost city” – is a guaranteed crowd-puller. The story of the Roman town destroyed by a volcano has resonated throughout the ages and is no less compelling today. It has an intrinsic drama that few historical exhibitions can match. Every item pulled from those ongoing excavations has a special fascination.

As new technology allows new forms of storytelling we can enjoy a more vivid sensory experience, but history cannot be transmuted into pure spectacle. The museum needs to cater to the casual viewer, but also to dedicated students of the ancient world. Such an exhibition provides a unique opportunity to push aside the tourist guidebook and engage an Australian audience on a much deeper level.

Pompeii: Inside a Lost City

National Museum of Australia, Canberra,

13 December 2024 - 4 May 2025

Published in The Nightly, 21 February 2025