On 9 December, the Nobel Prize winning economist, Paul Krugman, published his final opinion piece for the New York Times. As he explained in a subsequent article for The Contrarian, after 25 years “the nature of my relationship with the Times had degenerated to a point where I couldn’t stay.”

My eyes grew wide as I read this article, and one by Charles Kaiser in the Columbia Journalism Review that went into greater detail about Krugman’s departure. In the words of Monty Python, the Delphic oracle for our age, I was experiencing “that strange feeling we sometimes get that we've lived through something before” – Déjà vu. Bear with me while I trawl through a bit of recent history, now that I can do it in a more detached manner.

Krugman is a columnist I’ve read with interest for many years, enjoying his fluent prose, his commonsense opinions, his measured liberalism and a knowledge of economics that would leave most of us gasping. His description of what happened to make him lose faith with the NYT felt horribly reminiscent of my experience with the Sydney Morning Herald, a newspaper for which I began writing in 1983. I walked away from the art critic’s job on two occasions, for periods of four and six years, but was twice lured back. All told, I must have spent more than 30 years writing weekly columns.

“During my first 24 years at the Times, from 2000 to 2024,” Krugman relates, “I faced very few editorial constraints on how and what I wrote.”

It was only during the final 2-3 years of my working life with the SMH that I began to experience those “editorial constraints”, if you’ll pardon the euphemism. Up to that point, my writing was largely untouched. The editors trusted me to know what could and couldn’t be said within the limits of the law, and the subs appreciated the relative cleanness of my copy. I was edited for small errors and typos, but rarely was the substance of a piece questioned.

Krugman writes: “I came in at length, with clean writing and with back-up for all factual assertions.”

This was exactly what I tried to do. When I occasionally overwrote, I would argue for a little extra space, but ultimately take whatever cuts eventuated.

I use the word “column” by preference because I always considered that I was writing something more complex than a basic review. I wanted to provide a sense of context, history and topicality, to show how the visual arts were enmeshed within the greater culture. I reserved the right to an opinion when there were matters that demanded attention – most recently, the Powerhouse Museum debacle, the controversy over the APY Artists Collective, the terminal slackness of the Art Gallery of NSW, and the spendthrift ways of two successive directors of the National Gallery of Australia.

My feedback indicated I had a volume of readers who appreciated an independent, critical approach, but there was less appreciation from SMH management, where a new editor, who shall be known only as BS, was installed.

Over the course of three years, five art columns were left out altogether, others were sliced by up to a third. Almost every piece began to be edited in the most irritating, intrusive manner, sometimes changing the whole emphasis and thrust of a piece.

The excuse that Spectrum editor, Melanie Kembrey usually gave was that it was simply “a matter of space” – which never quite explained why the online version of a column had to be just as brutally sliced and diced.

I soon learned that artists who were Indigenous or Queer (caps essential) were all considered to be untouchable geniuses - if they didn't cross an invisible editorial line, as Bindi Cole Chocka did. A critical – but carefully argued – piece on Daniel Boyd’s show at the AGNSW was kept on ice for seven months, while the show enjoyed an unbelievably lengthy run. The story never saw the light of day. A piece on a Queer exhibition at the National Art School Gallery was left out, apparently in the belief that it might offend someone. This turned out to be true - it offended the curator, Richard Perram, who was furious the SMH had not printed the article.

And on, and on. I kept asking when we were going to write a decent investigative story about the Powerhouse or the APY crew, only to find the paper running puff pieces and one-sided stories that were no better than press releases. They were perfect demonstrations of the fallacy of “balance” in journalism. A balanced story is not one that goes: “he says, she says,” it’s a dialectic that takes in both sides and arrives at a credible conclusion. The goal is to ascertain the truth, not merely restate the claims of both sides, some quite obviously false or inadequate.

Krugman tells us that one of the turning points in his relationship with the NYT was a blog he ran as a supplement to his columns, which enabled him to discuss more “technical” economic matters. The paper killed the blog at the end of 2017. When he opened a Substack account in 2021 to fill the gap, “the Times management became very upset.” They agreed, instead, to publish a newsletter twice a week. This arrangement continued until September last year when they suspended the newsletter citing “a problem of cadence” (whatever that means!) and telling Krugman he had been writing “too often”.

For my part, the only thing that made my deteriorating treatment at the SMH bearable was my own website, johnmcdonald.net.au, on which I published the complete, unexpurgated versions of the articles the newspaper chose to censor. I also published an increasingly cranky newsletter, which has evolved into the piece you’re reading today, where I discussed the issues the SMH refused to touch, and told readers about my difficulties in getting material published. The SMH management asked if I would refrain from publishing the art column until it had been allowed a fair run in the paper. As a result, the SMH would run their version on Saturday, and I’d publish my version the following Tuesday. I’m following the same pattern with The Nightly, the main difference being that now there’s no substantive difference in what gets published on both platforms.

I knew the newsletter was making management nervous when Mel Kembrey asked if we could simply agree on a version of the article every week and run the same piece. I said this was easily done. All she had to do was print the article as I had written it. Problem solved! That seemed to put an end to the discussion.

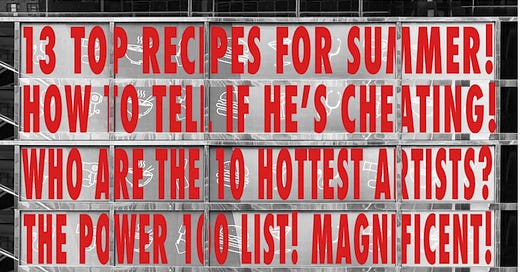

Mel, whom I had known as deputy editor of Spectrum, under Shona Martyn, had proven to be a great surprise to me. I’d previously considered her a friend. We’d even spent a day wandering around museums in Paris together. She told me, early on, that she was interested in me writing in a more essayistic manner rather than simply reviewing exhibitions. What I didn’t realise was that her idea of an essay was: “Who are the ten hottest young artists?” and similar topics that would have been at home on the cover of a womens’ magazine… “13 top recipes for summer”, “19 ways to tell if he’s cheating on you…” Somehow, it’s always a prime number.

Likewise, reviews of shows such as the Archibald Prize or Sculpture by the Sea, were not to be written in a discursive style, but presented as a list of hit picks, with about 100 words on each work. Some genius must have believed this would be more appealing to our readership.

It was becoming increasingly clear that Spectrum’s big fascination was “pop culture”, which they seem to have just discovered. As Andy Warhol said, “Pop is liking things,” and so we found the weekend pages full of trashy interviews with this week’s groovy new pop star, screen idol or writer. Or lists of what to watch, where to go, what to read, etc, for those who presumably had no clue about anything and were willing to take Spectrum as their gospel. In this setting, the art column struck an increasingly discordant note. It wasn’t always saying everything was nice. It asked questions rather than simply accepting whatever was found on a press release.

When Krugman wrote: “Also in 2024, the editing of my regular columns went from light touch to extremely intrusive,” I felt an instant sense of kinship.

He complained about rewrites that “almost invariably involved toning down, introducing unnecessary qualifiers, and, as I saw it, false equivalence.” He would be obliged to rewrite the rewrites, until “the end result of the back and forth often felt flat and colorless.”

I was rarely given the option of seeing an altered column before it went to print, although the changes were usually limited to cuts rather than rewrites. Sometimes whole paragraphs were chopped, often the changes were so petty, on such a micro-level, that an adjective would be removed from a sentence. When I quoted NGA director, Nick Mitzevich on the “magnificent” Tracey Emin” on which he had just blown a million dollars, the “magnificent” was cut. He said it, not me.

Eventually, I stopped looking at the version of the article that appeared in the paper because it was too depressing. Most of my editorial queries were avoided or left unanswered, until communication was virtually non-existent – a cowardly situation I’d never encountered with any other editor, over decades.

“I felt that my byline was being used to create a storyline that was no longer mine,” writes Krugman. “So I left.”

I wish I could say the same. Instead, I let this frustrating charade carry on for at least two years, until the editor known only as BS finally felt empowered to pull the plug in the most insulting manner, sending me an abrupt termination letter, giving me four weeks’ notice. I soon realised the SMH was going to “disappear” me, without a trace, and so made the announcement on my website. Literally hundreds of letters flowed to BS and his colleagues over the following few days, many of them cancelling their SMH subscriptions.

In retrospect I should’ve done a Krugman and pulled the plug myself, but I was in a groove at the SMH, where I simply carried on, week after week, putting up with the cuts and hoping for better times. I had no idea of the growing desperation to remove me from the art critic’s post which has since been filled by the lamest collection of ragbag articles by writers who seem to be qualified by diversity alone.

As a single example of the way my SMH articles were being altered I’ll cite the column on the NGA’s Emily Kame Kngwarreye retrospective, published on 15 December. I’m reverting back to the original spelling of the artist’s name, because it’s been made clear to me that this is the spelling Emily approved and wanted. The NGA’s new way of spelling her name is a posthumous imposition.

Although the review was measured, in its mix of praise and criticism, the inane headline read: If you want to understand Australian art, this exhibition is essential.

The main impression, taken from the concluding paragraph of the article, was that this was an “essential” exhibition. Next, the names of the curators, Hettie Perkins and Kellie Cole, were omitted when I asked why they hadn’t consulted Margo Neale, the curator of all the previous Emily surveys. Obviously, no-one could be identified where blame was to be assigned.

After discussing the snubbing of Neale, and Japanese curator, Akira Tatehata, who was almost single-handedly responsible for the landmark Emily surveys in Osaka and Tokyo in 2008, I wrote:

Not to acknowledge the work of one’s predecessors is at best unprofessional, at worst sheer discourtesy, especially when the catalogue incorrectly states that the 2008 show debuted in Canberra before it “subsequently” travelled to Japan. Surely the editors could have looked at the dates in the earlier catalogues, which remain the seminal reference works.

This was largely a statement of fact, pointing out that the NGA catalogue got the timeline wrong for the previous Emily shows. The entire paragraph was omitted from the SMH article.

Discussing the omissions from the NGA, I mentioned the artist’s last, poignant series of small works:

One of these works was felt important enough to be on the cover of the Japanese catalogue, but the NGA has completely ignored their existence.

This par was also omitted.

Trying to understand the reasons so many important works were left out of the show, I wrote:

In the Aboriginal art market, “ethics” has become a horribly rubbery concept that seems to benefit some at the expense of others. In place of a demonstrable fairness, there is often prejudice and favouritism. The only way to avoid this tangle is to concentrate on the works themselves. The very best paintings need to be included in any museum retrospective, regardless of who bought or sold them.

This became:

In the Aboriginal art market, the focus should remain on the works themselves. The very best paintings need to be included in any museum retrospective, regardless of who bought or sold them.

Another paragraph read:

Writers in the catalogue are concerned that we need a new vocabulary to understand the apparent ‘abstract’ qualities of Indigenous works that have precise meanings in the artist’s mind. It’s easier said than done, with even Cole and Perkins indulging a comparison with the American painter, Agnes Martin.

This too was omitted. The editor may argue it was just a question of “space”, but there is a clear pattern to the cuts and rewrites – namely, to remove any suggestion that the curators had failed to do their job properly by failing to consult or even recognise previous curators, substituting new ‘experts’ for those who knew Emily first-hand, allowing certain dealers to dictate terms in a way that injured the selection, and not detecting a basic error in the catalogue.

Why is this significant? Partly because the editor known only as BS had already declared himself to be a fanboy for the NGA and its “terrific” director, Dr. Nick. The SMH had previously run two weeks’ worth of puff pieces trying to get the government to cough up more money for the institution. It’s reasonable to assume that criticism of the NGA was not part of the BS agenda.

It's also significant because Tate Modern is on the verge of an historic Emily survey, and it’s a matter of urgency that the same mistakes and omissions not be repeated. The artist’s largest painting, Earth’s Creation, and that amazing series of last works must be included in the show, or international audiences will not see Emily at her best. If Tate Modern is complacent enough to accept the NGA show without major revisions it would constitute a serious misrepresentation of the artist’s work.

When Krugman writes: “it became clear to me that the management I was dealing with didn’t understand the difference between having an opinion and having an informed, factually sourced opinion,” I felt he was writing my valedictory address to the SMH, had I been allowed to write a final column rather than being snipped off so abruptly.

As if this wasn’t enough, another article was recently brought to my attention, which discussed the experiences of Dr. Eric Reinhart, who was asked to contribute a piece to the Los Angeles Times on Trump’s nominee for Head of Health and Human Services, Robert F. Kennedy. His assessment was originally titled "RFK Jr.'s Wrecking Ball Won't Fix Public Health." However, Times editors ran the article under the title, "Trump's Healthcare Disruption Could Pay Off—If He Pushes Real Reform."

He accused the editors of “editing out a very central and timely point in the minutes before sending to press while then also assigning a title and image that suggest an argument entirely opposite to the author's clear intent.” The blame was swiftly shunted back to Patrick Soon-Shiong, the bio-tech tycoon who has owned the LA Times since 2018 and has publically declared himself a fan of RFK.

The point of these stories – from Paul Krugman, Eric Reinhart, and yours truly – is that they all paint the same depressing picture of a major newspaper giving up on its role to present a broad range of news and opinion. The American media is caving in to its right-wing critics, bending the knee to the mad emperor, Trump, and his billionaire buddies. The SMH is neutering its coverage of arts and politics, perhaps in an effort not to offend NINE’s potential advertisers, but also because it lacks the moral courage, and possibly the resources, to do the right thing. I was a pretty cheap date for NINE, but I persistently refused to praise the things BS thought were cool, as he ignored a mountain of evidence to the contrary.

When the Fourth Estate voluntarily relinquishes its social, cultural and political power, choosing to persecute dissidents in its own ranks, our democracies are in trouble. Is there any turning back from this sinkhole of mediocrity in which the media is voluntarily immersing itself? We can always hope, but one suspects it will get a lot worse before it gets better, as papers such as the SMH see further dumbing down as their only solution to falling readership and revenue.

The art column for The Nightly, this week, looks at Marikit Santiago’s survey, Proclaim your death!, at the Campbelltown Arts Centre. Santiago has increased her visibility enormously over the past couple of years and must be seen as one of the emerging talents in Australian art – even allowing for the fact that almost all her paintings are obsessed with the history and mythology of the Philippines, the country from which her parents migrated. Personally, I don’t see why Australian art can’t be organically connected with the Philippines or any other country. Art today is a global affair, and Australians cannot afford to be insular in their tastes.

The movie being reviewed is Halina Reijn’s Babygirl, which features a daring, controversial performance by Nicole Kidman. I haven’t always been a Kidman fan, but I’ve changed my mind with this film, which is absorbing, if not always comfortable viewing.

After only one week, Hazel Dooney has changed her mind about running a Digital Strategies column on this site. We’ve decided to keep the focus on art, film, and general cultural matters, while Hazel writes for her own Substack site. We both understand that navigating the Internet is increasingly complex and it’s easier to find one person’s work on their own site, under their own name. In the meantime, Hazel continues at Everything the artworld doesn’t want you to know as resident techie and strategic advisor. As the site is still relatively new we’re willing to experiment and lay plans for the future. The abject failure of the mainstream media opens up a world of possibility for independent voices.