With a retrospective at the National Gallery of Australia, and a brick of a catalogue, Ethel Carrick (1872-1952) is finally having her moment, yet this march into the limelight entails a separation from her husband, Emanuel Phillips Fox, an artist of skill and subtlety whose reputation has never diminished. When Mannie died in 1915, at the age of 50, mere days after being diagnosed with cancer and undergoing an operation, Ethel was devastated. She may have felt especially gulity because she was in Sydney at the time that he was hospitalised in Melbourne.

From here on she would sign most of her canvases “Carrick Fox” and work tirelessly to ensure Fox’s paintings were shown and collected by the art museums. Previously she had been happy to stick to “Carrick”, as we learn from a review of 1908, quoted in the NGA catalogue: “In her aims and methods Mrs Fox, who exhibits under her maiden name of Miss Carrick, is distinctly of the advanced school of Impressionism.”

While the mind boggles at how any Australian reviewer of the time understood the “advanced” school of Impressionism, we recognise Ethel as an independent spirit – perhaps one of those ‘New Women’ who frightened the life out of the male characters in Victorian novels. With Fox’s sudden death she became a dutiful widow, even as she continued to paint and travel with boundless energy.

The NGA has been politely questioned as to why they have preferred the name “Carrick” to “Carrick Fox”, when the artist herself seems to have used the latter continuously during her 35 years of widowhood. As the marriage lasted only 10 years, there’s a fair argument that Carrick deserves a show “in her own right”, with no disrespect to Fox. It’s also much simpler to stick with the same name from start to finish, rather than changing tack according to the signature on each painting.

The nomenclature would probably not have been an issue, had it not synched in with the NGA’s endless Know My Name project, which aims to bring ‘neglected’ women artists into the light. Like everything at the NGA under Nick Mitzevich’s leadership, it’s one of those funky ideas that has been extended beyond its use-by date. As the program has been going for five years, by now even dedicated femocrats might be feeling that the point has been made.

It's a bit like the SaVĀge K'lub installation that got the NGA into trouble last week. What began as a cool idea to accompany the Gauguin show, has been left lingering long after the blockbuster moved on. Eventually someone noticed that a few small Palestinian flags had been covered over with white patches, and cries of “Censorship!” resounded around Australia. It was another attempt to have one’s cake and eat it: posing as a champion of Postcolonialism, while quietly removing the bits that might embarrass your master, the government. Ultimately, as Bob Dylan sang, everybody must get stoned.

In Carrick’s case, the catalogue, in which the main, biographical essay is written by curator, Deborah Hart, contains seven further essays by female contributors. Would it have been acceptable to have a catalogue on a male artist with only male writers?

As anybody knows who has ever tried to read the novels of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, too much virtue can drive one to distraction. It’s time the NGA resumed normal service.

Despite these grumbles the good news is that Ethel Carrick is an impressive exhibition which brings this work to life like never before. Hart has researched her subject with great thoroughness, selecting 140 pictures that trace the artist’s career from her early days in London to late works painted in Australia and the south of France. The vibrancy of Carrick’s palette (we’ll call her “Carrick”) and the vigour of her brushwork remain intact until the end, even if her very best pictures were made in earlier decades.

A portrait emerges of a hard-working, assertive personality, who never allowed her gender to pose an insuperable obstacle in a male-dominated art scene. In Fox, Carrick found her perfect complement – his conservative tendencies balancing her radicality; his sense of tradition tempering her urge to experiment. They disagreed about many things but also learned a great deal from one another.

.

They were never closer, in painterly terms, than on a trip to North Africa in 1911, when they worked out-of-doors, side-by-side, making quick oil sketches in the streets. Fox loosened up, while Carrick painted with remarkable freedom. Her Laveuses algériennes (Algerian women washing clothes in a stream) (1911), is one of the highlights of this exhibition – a virtuoso display of rapid-fire brushwork, with a high-keyed, predominantly yellow palette.

Nowadays we think of Carrick as an Australian artist, but she was English by birth and a citizen of the world by inclination.

Born in Uxbridge, on the outskirts of London, into the family of a prosperous storeowner, Carrick was allowed to follow her vocation, studying art at the Slade School, from 1899-1904. She was almost 30 when she met Fox on a painting excursion to Cornwall. The couple would marry in 1905, and move immediately to Paris, setting up home in an artists’ studio complex in Rue Arago.

Carrick embraced the creative ferment of the Belle Époque, working quickly in a Post-Impressionist manner. In her large painting, The breakfast table (c.1907), she is still in Slade School mode, working with a delicate play of tones, each object carefully delineated. The broken light that filters through a blind would remain a source of fascination, but in her smaller paintings, she had already given up on the subtle modulations. She would capture a flicker of sunlight with a thick dab of white.

One can feel the excitement with which Carrick plunges into her work in the period before the First World War. Catalogue essayist, Jenny McFarlane, suggests these were the best days of the artist’s career, and it’s hard not to agree. She was mixing with some of the leading figures of the age, exhibiting in the Salon d’automne, where the Fauves made their sensational debut in 1905, becoming a associate in 1911 and a jurist in 1912. In the latter role she would sit in judgement on her husband’s entries.

At this time Carrick was included in major group exhibitions and written up in influential magazines. Through her interest in Theosophy - that ersatz blending of world religions that attracted so many artists, writers and composers - she met and mingled with the most innovative modernists. When we look at Carrick’s vigorously brushed pictures of people in the Luxembourg Gardens, we don’t think of artists such as Kandinsky, but that was the milieu in which she was moving.

McFarlane stresses that the Theosophical emphasis on “vibrations” played an important role in the way Carrick conceived of her paintings, as she sought to capture energy and movement. Her favourite subject was the crowd, with its miriad rhythms and personalities.

When she travelled to Australia for the first time in 1913, Carrick brought all this energy along with her, plus a collection of recent works. She must have felt distinctly out-of-line, as nobody in Melbourne or Sydney was painting in this manner. Rather than toning it down, she set out to make local taste conform to her priorities.

She travelled by herself back to France in 1916, while the conflict was still raging, and suffered the privations of life during wartime. The paintings she made at the end of the war are the saddest things in this show. Place de la Concorde (c. 1918-19) presents a dull-toned vista of shadowy figures roaming around this famous part of Paris like lost souls under a cloudy sky. The sun strives to provide rays of hope.

As her good spirits returned, Carrick went back to those places she had enjoyed painting in the past – the busy French gardens and markets. One of the outstanding pictures from this time is The market (1919), which sold for $1.46 million at auction in 2019. A fount of colour and visual anecdote, the most appealing feature may be those signature bursts of white that show sunlight breaking through the canopy of trees.

When Carrick returned to Australia it was in 1925, for a Theosophical congress. She would stay for two years, establishing her presence in the local art scene. For the rest of her life, she travelled back and forth between Australia and Paris, making lengthy side trips to North Africa, India and many parts of Europe. If we now view British-born Carrick as an Australian artist, we need to recognise that her commitment to this country probably diminished her recognition in France. A high point came in 1927, when a modest painting of a flower market in Nice was acquired by the French state. She was 55 years old.

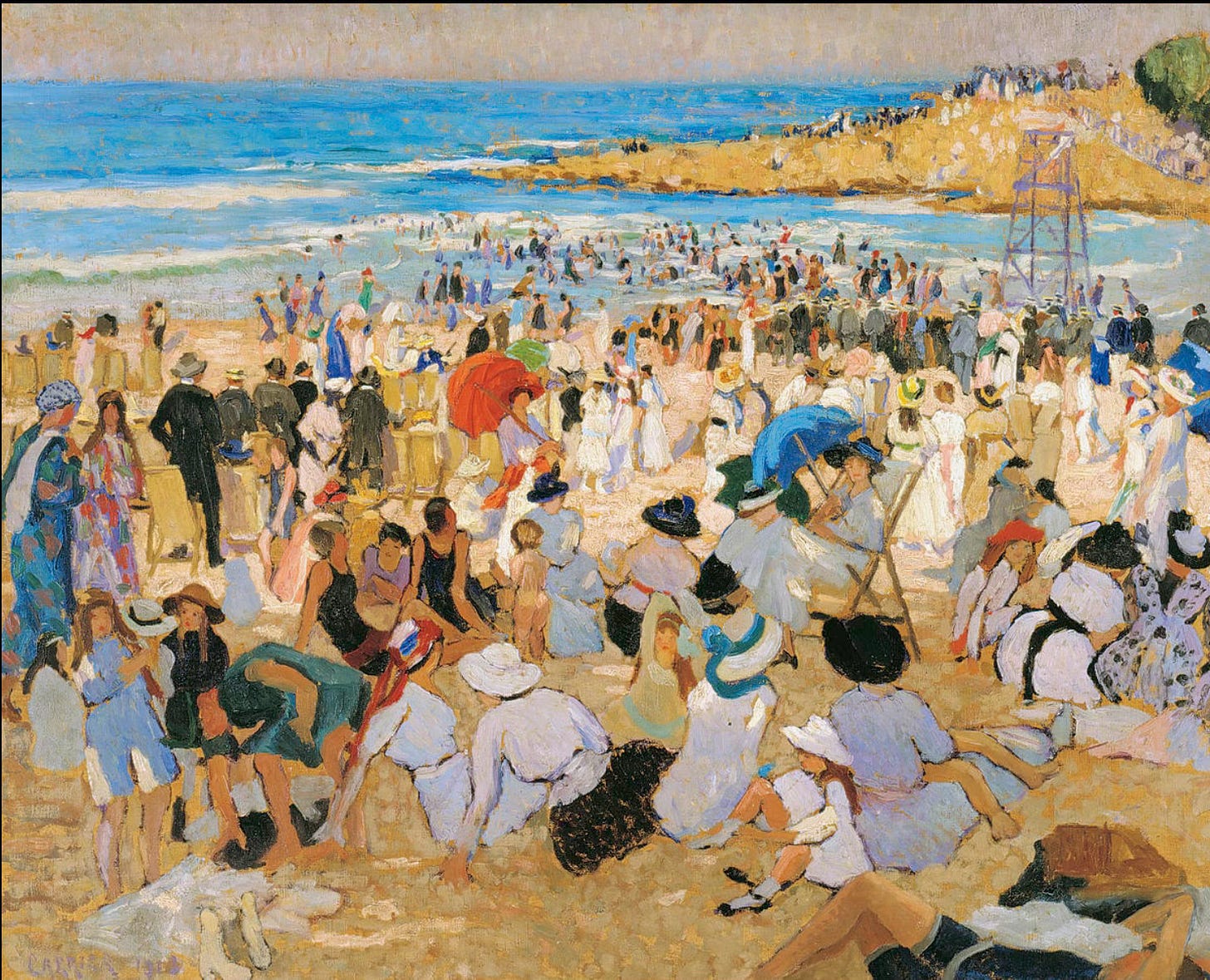

In the same year she was awarded a diplôme d’honneur at an exhibition in Bordeaux for Christmas Day on Manly Beach (1913), a painting generally acknowledged as her masterpiece. It’s surprising to find Carrick exhibiting a work she had painted in Australia 14 years previously, but also that such an important picture had remained in her possession for so long. We look at this exuberant scene of people enjoying themselves on a crowded Manly Beach and feel an almost visceral thrill at how well the artist has captured the colour and atmosphere. But this was not the way many contemporary viewers saw the work. All the things we enjoy – the bright colour, the spontaneity, the quasi-abstract play of forms – would have been causes for concern, signs of a modernist sensibility that potential buyers found hard to handle.

The French had no such qualms. Around 1927, Carrick would paint another outstanding picture - The Fruit market, Nice (c.1927), a lively canvas on which crowds, umbrellas, spindly trees and buildings are arranged in distinct layers of imagery. It’s a crammed composition, but so cleverly structured it feels almost classical. The colour highlights are used in a fresh, economical way to add a sense of animation.

The exhibition takes us through the work Carrick made during the Second World War in Australia, where she spent much of her time helping to raise money for France and working in a voluntary capacity on the home front. We continue with her post-war travels around Europe and Asia, where age and arthritis never prevented her from venturing into the most out-of-the-way places. Finally she returns to the markets in Nice, painting people in the fashions of the early 1950s rather than the long skirts of the Belle Époque.

Carrick comes across as an indomitable character, but most of the works she produced over those last years were small, and almost wilfully minor. These pictures are always appealing but would never allow one to make a case for her importance. She was a compulsive artist who had her greatest moments in the years before World War One, when she became caught up in the excitement of a time of change; and in the years after the war, when she attained a maturity that led to some of her most impressive works.

Had she never left Europe, Carrick may have made a more lasting impression on the French art scene, but history suggests that Australia became her surest path to fame. When Post-Impressionists were thick on the ground in Paris, they remained a rare species in Australia. In committing herself to her adopted country, Carrick brought a touch of modernist sophistication to a conservative, inward-looking culture. We can all be grateful for the choice she made.

Ethel Carrick

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra,

7 December 2024 - 27 April 2025