This week I made my usual rapid trip to Canberra to see four exhibitions: Pompeii at the National Museum of Australia, Carol Jerrems: Portraits at the National Portrait Gallery; Ethel Carrick and Anne Dangar at the National Gallery of Australia. I’ve written up the Jerrems for this week’s art column for The Nightly, because it finishes soonest. The other shows are in the queue.

What did I find? The NMA was full of people. Even the carpark was packed. The NGA was more sparsely attended, although Carrick and Dangar seemed to be attracting a steady trickle of visitors, while the NPG was virtually empty. There’s nothing scientific about these observations, which could have been affected by many factors. The NPG, for instance, is significantly smaller than the other museums, and offers fewer options.

Ignoring the variables, the simplest conclusion is that the majority of museum goers still want to see the ‘blockbuster’ touring exhibitions. Pompeii is a package show put together by the French and the Italians, that features artefacts in glass cases, audio-visual presentations, interactives, and much educational material. Carol Jerrems, by contrast, is pitched as a new look at an Australian photographer of the 70s who has attained a cult-like popularity – at least among curators.

The Carrick and Dangar shows are historical surveys of two wellknown female artists worthy of in-depth investigation.

The writing associated with the Jerrems show is a perfect example of where ‘art history’ is heading today. The essays are impressionistic and largely subjective, with lavish use of the first person singular. Instead of hard facts about Jerrems or credible interpretations of her work, we learn how the writer feels about the artist – the implication being that we, as readers and viewers, are invited to make the same kind of personal associations.

There’s a place for this kind of writing, but it’s a small place. The idea that one commissions a contribution by a writer of some description who has no special association with the topic, and hopes for the best, is a lucky dip. Even the terminology is becoming increasingly modish. I’d be delighted to find writers using the term “Aboriginal” or even “Indigenous”, rather than “First Nations” – a term that means nothing to the vast majority of artists who live in the so-called remote communities, where the preferred terms are “Aboriginal people” or simply “Blackfellas”.

In relation to sexual identity, where relevant, it would be good to find words like “homosexual” or even “gay”, rather than the current buzz word, “queer”. This term, which has been reclaimed of late, is far too easily associated with a political stance of perpetual opposition, gender fluidity and other issues that belong to the present. Used in an historical context it tends to distort our view of an artist’s personality and biography, transforming conservative figures into quasi-radicals. When I think of “queer” I think of Judith Butler, the controversial US intellectual whose views on sex, gender (and Gaza!) are as problematic as they are influential. Art history, a field with a long, distinguished pedigree, should not be so easily Butlerised. As for the vogue of including everyone’s AOs, AMs, doctorates and sundry titles into essays, this is a tedious formality that should be abandoned forthwith.

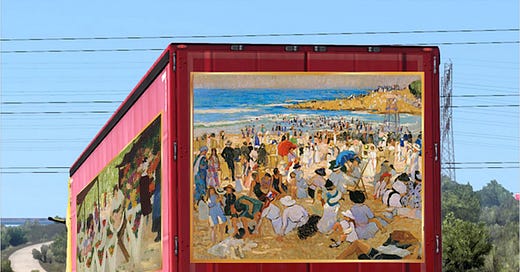

With the Ethel Carrick show, one fascinating sideline has been a YouTube presentation by Leigh Capel, which provides an object lesson in art historical methodology, as this young researcher tries to understand why the artist is not being referred to by her more familiar name, “Ethel Carrick Fox”.

Capel assembles his evidence to make a persuasive case that “Carrick Fox” became Ethel’s preferred name upon the death of her husband, Emanuel Phillips Fox (1865-1915), whom she outlived by 35 years. He even shows how Ethel would write “Fox” at the end of her signature on older paintings.

The implication is that the NGA decided it would do Ethel a favour by removing the name of the abhorrent husband, regardless of how she actually wanted to be known. This could be perceived as a slight against Emanuel, who must be counted one of the most well-loved figures in Australian art history, and a denial of Ethel’s personal wishes.

Deborah Hart, the curator of the Carrick show, is horrified at the suggestion, which she claims was never her intention. She argues that the names “Carrick” and “Carrick Fox” have both been used extensively – and that sticking to the artist’s birth name was a matter of convenience. The principle, one might say is that of Ockham’s Razor – when in doubt, choose the simplest option.

I completely understand this point of view, and have the greatest respect for Hart, an old-school art historian who has done a phenomenal job with this exhibition. But Capel’s claims, respectfully couched, are not easily dismissed. He even managed to dig up Ethel’s last will and testament in support of his argument.

The main point is that Hart and the NGA should be delighted that an independent researcher has gone out of his way to investigate one aspect of this exhibition. A major retrospective is an open invitation to discover previously unknown facts about an artist, to resolve lingering dilemmas, to better understand her influence and sources, her personal connections and place in history. The controversy over Ethel’s name is a tribute to the seriousness in which Capel has approached this show, and the hard work put in by a curator who is anything but an ideologue. It’s exactly what one wants from an exhibition, as opposed to a lot of airy essays telling us how a writer feels about an artist.

If we stop and wonder why everyone was so ready to believe the “Fox” had been deleted from Ethel’s name for more nefarious reasons, Capel has an answer. He points out that over the past year the NGA’s Know My Name project has resulted in 84% of NGA programs being devoted to women artists. This goes beyond affirmative action and raises questions about how the national collection is being represented. To swing the pendulum so drastically in the opposite direction is to distort the public view of the gallery’s holdings and art history in general, imposing a filter that edits out many important works by male artists. It’s over-the-top, leaving the gallery authorities open to accusations that they are more concerned with virtue signalling than showing the very best of the collection.

More adventures in art history are to be found in Adelaide, where Henry R. Lew, a prolific, amateur art historian, has spent years fuming that Carrick Hill has reattributed a painting by the Australian artist, Derwent Lees (1884-1931), to Welshman, J.D. Innes (1887-1914). This may seem a trivial issue to some readers, but it has rendered Lew incandescent with indignation.

To understand his outrage, one must first understand that Lew is by profession, an ophthalmologist, who has researched, written and self-published a succession of art history books because of his passion for the subject. He is a maverick in the field, not associated with any institution. The suspicion arises that his outsider status renders him suspect with professional curators, directors and managers of museums and galleries.

His concern is that a work in the Carrick Hill collection, Derwent Lees’s Chateau Royal, Collioure (1913), which appears on the cover of his book, In Search of Derwent Lees (1996), and is in his opinion, “perhaps the best painting in the entire collection”, is no longer attributed to the artist. The reattribution was made by British art historian, John Hoole, who in 2013 published a catalogue raisonné of J.D. Innes, who died at the age of 28. Both Lees and Innes were protégés of Augustus John, and knew each other well.

Lew points out that the reattribution of two paintings was made on the basis of their being unsigned. Chateau Royal, Collioure (1913), was not only reattributed, it was retitled Fishing boats, Collioure, and redated to 1911.

Lew is flabbergasted that Hoole has never actually laid eyes on these paintings, knowing them only from photographs and entries in exhibition catalogues. If this were the sole point of contention it should set off alarm bells. Leigh Capel’s argument about Ethel Carrick (Fox) is grounded in careful first-hand examination of her works, while the crazy scandal of 2022, in which journalist Gabriella Coslovich accused the NMA of accepting a dud painting by Rover Thomas, drew on testimony from five “experts” who had never seen the actual painting.

In matters of attribution, there is no substitute for the first-hand examination of a picture.

Accordingly, in 2015, Carrick Hill asked local curator and art historian, Jane Hylton, to look at the reattribution. She did so and affirmed Innes as the artist. Lew asks, with barely concealed impatience, how Hylton, known for her work on Australian women artists, could have sufficient familiarity with the works of Lees and Innes to contradict his years of painstaking research.

He says he is frustrated by the reluctance of the Carrick Hill authorities to allow him to discuss and debate this matter with Jane Hylton. He has also approached John Hoole, who is equally unwilling to debate the attribution in a public forum. I spoke with Hylton, who has retired from curatorship and art consultancy, and is now working as an artist in her own right. While she has no desire to get back into the ring, Hylton says she supported the attribution to Innes on stylistic grounds, and because the original purchase documentation pointed in that direction. She also says that when she put the two artists’ work side-by-side, the painting looked so much more like Innes “it wasn’t even funny”. She has no regrets about her decision but says if the opposite case can be proven that’s fine.

This will not satisfy Lew, who, as an ophthalmologist, has perceptual evidence to back up his case, in the “Hubel and Wiesel” technique he has championed in at least two volumes. I’m not about to enter into the technical side of the discussion but his point is that certain artists can be distinguished by their manner of laying down painted lines to create a more vivid illusion of life. Lew notes that Hals and Velazquez are such artists, as is Derwent Lees, but Innes is not. The case is made, exhaustively, in his books, Australian Genesis and Exodus (2023) and Imaging the World (2018).

By this point you’re probably wondering is Lew is the real deal, or one of those obsessive ratbags with a theory, who is the dread of every museum director. He’s certainly a man obsessed, but he has such a weight of evidence and argument on his side that it seems impossible to blandly dismiss his claims. On what basis? That he’s an amateur art historian? That John Hoole is English, and therefore more likely to be correct? That Jane Hylton, as a former curator at the Art Gallery of South Australia, has better professional credentials? It may come down to a simple matter of perception. Hylton looks at a painting and sees Innes, Lew sees only Lees. Are the eye-doctor’s perceptions reliable? Can the mind shape what the eye has grown accustomed to seeing?

Reattributions have powerful knock-on effects for an artist’s reputation, their place in art history, and their auction prices. The NMA conducted a comprehensive investigation into Gabi Coslovich’s dubious accusations about Rover Thomas, which carried on beyond the point when it was obvious there was nothing fishy about the bequest. Even if Carrick Hill believes Henry Lew to be nothing but a pest, they need to broach his accusations with equal seriousness and settle this matter once and for all. Art history is too important to be treated in a careless fashion, allowing the truth to be whatever one prefers, rather than the result of thorough research and debate.

In politics, and most other walks of life, we’ve developed the appalling habit of just going along with whatever we like, rather than what we know to be true. The rot should not be allowed to seep into the data bases of our museums, where information must always take precedence over opinion.

This week’s art column, as noted, looks at Carol Jerrems: Portraits at the NPG, while the movie being reviewed is the Bob Dylan bio pic, A Complete Unknown. There’s plenty of dubious history in this entertaining film but nobody could ever expect Hollywood to stick to the same standards of accuracy we require of our art museums. Instead, we might ask the museums, respectfully, to be a little less like Hollywood.

Great article John. And while I have your attention, you should check out the new show by artist Merrick Fry when it opens in Buckingham Street Surry Hills this March. I've seen it at his Annandale studio and it's brilliant. The focus is on Aboriginal massacres (Myall Creek etc). This might be his magnum opus.

Loved reading about Carol Jerrems ... She loved - both physically and spiritually - every Artist from the 60s in Sydney and Melbourne in unforgettable ways XXX